How stories and feelings dominate over facts

Reading time: ca. 17–25 minutes.

By Levien van Zon

When talking about sustainability, we often assume that people behave “irrationally” because they are badly informed. Or perhaps they are selfish, or incapable of thinking about long-term consequences. Some or all of these things may be true for some people, but I don’t think that this explains very well what’s going on. In this article I want to show that the way the human mind works is often misunderstood. Rational thinking isn’t our default mode, and better information doesn’t necessarily change the way we think about things. If we’re interested in positive change, we should be more aware of what really goes on in our heads, and how this interacts with what other people think and do.

The shape of thinking

How do you experience your thoughts? This may seem like a silly question. I had always assumed that the experience of thinking would be more or less the same for everyone. Recently I started asking other people about their inner experience, and I was quite surprised to discover that my own is far from universal. The problem is that I only have direct access to my own conscious mind. My “stream of thought” is both auditory and visual: I am aware of an inner voice that constantly talks about my experiences, inferences, plans and feelings. On top of this, I literally see memories and abstract concepts as static or moving images and spatial structures. It is likely that the way you experience your thoughts will be quite different. Yet if I would ask you to look back on your life, you would probably do so in a way similar to me and most others: You would experience and describe your life as an evolving story.

Rationality and its problems

Humans employ more than one mode of thought about the world and our role in it. When we talk about “thinking”, we often mean “rational thought”, a mode of thinking that involves conscious attention. It is guided by reasons, evidence and consistency. Rational thinking is important and powerful, but it does have its limits. In the previous two articles I argued that the social and natural world we live in is largely complex. This means that processes can be strongly entwined, making them hard to understand and hard to predict. Such complex systems cannot be fully controlled using rational planning. Rational thinking is still very useful, but it does have difficulty with complexity. One reason is that conscious thinking requires attention, which we can only focus on one thing at a time. This is a problem if many different things interact. Conscious thought also depends on working memory, which can hold only a few items. And crucially, for most of its tasks, our mind does not even rely on conscious processing, let alone “rational” thought.

Of course the modern world does strongly rely on rationality. Fields like philosophy, engineering, mathematics, statistics and the sciences have been extremely important in shaping the world that many of us depend on. But these same fields suffer from issues of attractiveness and accessibility. Science and similar pursuits require logical, procedural thinking, which takes effort and often requires a fair amount of prior knowledge. But perhaps more significant is that these fields are far removed from the lived experience of people who aren’t scientists or philosophers, i.e. most humans.

Most people are not very interested in abstract or technical subjects. What do we find attractive instead? Stories, especially stories that do closely match our lived experience, or that expand it in some meaningful way. Attractive stories tend to be about people and about their goals and feelings. Expository texts like the one you’re reading now, which discuss abstract concepts or detailed knowledge, are inherently much less attractive to most people. You can most likely read and understand this text without too many problems, but you may still have put off reading it. And it may take you some effort to get to the end, while this is much easier when reading a novel or watching a series. The relative unattractiveness of abstract ideas can be a problem, because we do need abstract thinking and technical knowledge to solve important human problems.

Rational, irrational, unconscious

In the context of sustainability, you often hear the argument that we all just need to be more rational, especially about our long term behaviour. There is an implicit assumption that if we just give people better information, they will make better decisions. But contrary to what much of economic theory assumes, humans are not logical, rational computers. And from the perspective of neuroscience, all forms of thinking involve processes that we could consider “irrational”.1

Most of our thinking is unconscious and biased. All of our thoughts are influenced by our feelings, by social relations and by culture. Even our conscious, “rational” thinking is not necessarily based on empirical evidence or on strictly logical argumentation.2 And there are good reasons for all of this. If you really want to make better decisions, or help other people to do so, having good information is certainly useful. But it isn’t sufficient. It also helps to be aware of how your mind actually works, so you can better use its strengths and guard against its weaknesses. And as we shall see, stories deserve special attention due to their unique role in conscious thought.

The world in our heads

First let me come back to my initial question, how do we experience our thoughts? My thoughts are accompanied by visuals and a clear inner voice. Most people seem to have an “inner narrator”, but it is not always present and can take various forms. Some people literally hear a voice, sometimes their own, sometimes a different voice, sometimes more than one. Other people see written text, and deaf people might see hands performing sign language. In a 2021 article in the Guardian, one lady reported her inner voice was actually a dialogue, involving a radio host asking her questions. Someone else reported that her inner experience included a kitchen, in which a bickering Italian couple argued over her thoughts. Some people rarely think in language at all, instead they experience images, tastes, signs, sounds, colours, feelings or other non-symbolic experiences. Some lack even that, they experience mostly inner silence. However, having no inner voice or visuals doesn’t mean that you have no thoughts. It just means that you aren’t conscious of what your thoughts are.3 In fact most thinking is unconscious, for all of us. The thoughts that we consciously experience are only a small tip of the mental iceberg.

The form in which we become aware of our thoughts can differ greatly between people. The content of our thoughts turns out to have a much more common structure. Our conscious thoughts often revolve around our goals and around feelings (those of ourselves and those of others).4 Even our unconscious thought is driven strongly by goals.5 These goals in turn reflect our needs and our values, the things that seem important to us at a given moment.

Fast and slow

One of the better known models of human thought was formulated by the late psychologist and behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman. In his best-selling book Thinking, Fast and Slow he distinguishes two broad mechanisms for thinking. One he calls System 1, which is fast, efficient and mostly automatic. It depends on unconscious knowledge and skill. This roughly corresponds to what most people would call intuition. The other mechanism he calls System 2, and it corresponds to deliberative “rational” thought. This mode of thinking is slow, costly and it requires sustained effort and attention. We mostly rely on the fast processing of System 1, and we only invest in the “System 2” effort of slowly working through information and arguments if we feel we really need to.

Kahneman’s model is probably a bit oversimplified, but it is useful and it does highlight an important biological reality: We humans may have big brains, but we still have limited mental resources, and these are costly to employ. Where possible, our brain takes shortcuts and simplifies “reality” for efficient processing. Mostly we are not aware of this. We usually regard our internal representation of the outside world to be complete and accurate. But when constructing a model of our environment, our brain ignores information that is deemed irrelevant, and it fills in bits that seem to be missing. Constructing a full and accurate model of our surroundings would be way too costly, so our brain aims for something that is “good enough”.6 This is why we don’t see our nose, why optical illusions work and why we can easily be fooled by magic tricks.

In addition to simplification, automaticity is also essential. If we would need to consciously decide on everything we do, including which muscles to move in which order and how to navigate through space on two legs, we wouldn’t get very far. We would probably never get out of bed. This is why the coordination of our muscles and our senses mostly happens automatically. Walking on two legs isn’t easy, yet we generally manage to learn it (after a somewhat awkward training period in early childhood). Once we have learnt complex coordination skills like walking, cycling, driving a car or playing an instrument, they no longer involve conscious thinking. And in the name of speed and efficiency, many other mental tasks are handled automatically and unconsciously as well. This makes sense, because conscious processing requires attention, and this cannot be applied to many things at once. We direct our attention at things we are interested in, but attention can also be directed by mechanisms outside our control.

There is a fish in the percolator

Two situations can powerfully grab our attention. One is surprise, which happens if reality does not seem to match the predictions generated by our brain. This requires that we pay more attention to details and figure out what’s going on.7 For instance, what’s this weird section heading doing here? Should I still drink the coffee?8

The other attention grabber is feeling, which is a conscious signal emitted by our unconscious mind, often indicating a need for action. The nature of the action required is indicated by the kind of feeling. For example, bodily sensations such as hunger or thirst tell us that we need to eat or drink, which in turn requires us to go search for food or water.

We also have feelings about the external environment. These are a bit more complicated (because they are coupled to emotions)9, but they have the same basic function: They direct our attention to possible needs, to things that may be important. By pointing out needs, our feelings strongly determine our short-term goals. Fear tells us we are in danger, and we may need to hide or run away. Anger tells us we may need to fight. And positive feelings tell us we’re safe and we can rest or play. The way feelings and emotions work seems to be similar across many animal species.10 But social animals such as ourselves seem to possess strong social feelings as well.11 These address our existential need to be part of a group.

Feelings are probably the most direct driver of behaviour in all animals, including humans. They indicate acute needs, but they are fleeting experiences. They wear off once a need is met, or when it is perceived as less acute. Feelings are not permanent and can rapidly be displaced by other feelings. So how then do we determine and pursue long-term goals? This is where stories and our social environment come in.

Organising experience

In essence, a story can be thought of as a coherent ordering of selected information in time. Most people will associate story with fiction: think novels, movies, theatre, song lyrics, fairy tales and myths. But story is much broader, it also includes biographies, documentaries, personal recollections, conspiracy theories, gossip, advertisements, expressions of ideology, explanations and in general any description of the past or the future. Stories owe their familiar shapes to recognisable patterns of events that we call plots. Stories seem to be an inherent form that our mind imposes on our conscious experience.12

Our brain constantly works to impose order on the flow of experience. If certain events predictably seem to follow others, we automatically infer cause and effect. When we look back on our experiences, we do not access a faithful recording of everything that happened. Rather, our brain selects certain memories and it ignores others. We tend to prioritise memories that are somehow relevant to our feelings or goals, although this is not something we do consciously. Moreover, the memories that we recall are not separate, unconnected snapshots, they get ordered into familiar patterns. When we listen to music, we do not experience a song as separate, unconnected notes. Similarly, we experience our memories as a kind of coherent story, often with a plot that revolves around our intentions, or those of other people.13 Our memories are not recordings but mental re-creations, which are edited by our unconscious mind to make sense to us.

To remain sane, we humans need our “life stories” to be coherent and to follow a storyline that feels familiar, in which our lives have a direction. This is where long-term goals are important. In a sense, each of us creates a personal myth by which we orient our lives. This is no static narrative, it is constantly revised as our life progresses. But we do closely guard its coherence. We unconsciously select which information is included into our life story and how it is interpreted. Everyone does this, but the process of selection and interpretation is easier to see in other people than in ourselves. We all know people who seem to spin memories and facts in ways that benefit their own self-image or their optimistic outlook, or less helpfully, that perpetuate depression, addiction or questionable lifestyle choices. And again, they are not usually aware that they do this.

We contain multitudes

Talking about a “life story” or “personal myth” may give the impression that we value consistency over everything else. But humans are rarely consistent. Our behaviours, opinions and rationalisations are full of internal conflicts. They can shift all the time. We do not have a single life story. Actually we maintain many versions, which we employ in different contexts. In other words, we can be slightly different persons, employing a different “narrative identity” depending on our situation. At work we present a different version of our “self” than when we are among old friends. And the “self” talking to our mother will differ from the “self” that flirts with someone attractive. Our narrative selves can have different goals in different social situations, and we will thus highlight different aspects of our history and our character. We can even have different values: the things we consider important can change according to who we are with. Unhelpfully, our values in one social context sometimes contradict our values in another context. This doesn’t make us hypocrites, it just makes us human.14 We adapt our behaviour to the people around us because other people matter to us. In fact, it is hard to be a “self” on your own. Your conscious thinking and the elements that make up your life story all depend on the ideas and stories that are available in your environment. And we also use other people to calibrate our moral compass.

Messy morals and shared stories

Morality is complicated, messy and absolutely central to how human social groups are held together. Moral behaviour is guided by cultural customs and by the rules of ethics. Explicit moral rules are encoded in legal systems and religious texts. In practice, morality also depends strongly on intuition and feeling. We have strong feelings about fairness and what constitutes “right” or “wrong”.15 What we consider “good” is determined mostly by our social environment, by the fundamental values of the people we feel connected to. Such values outline which actions are desirable or unacceptable and what constitutes a rich, meaningful life, as opposed to an empty, meaningless one.16 Shared stories are important in this, they communicate shared values, goals and expectations. We can choose to align ourselves with these, or we can oppose them.17 But whichever choice we make, we are not isolated individuals with purely independent goals and feelings. Instead we are more like actors, engaged in various plots in a world of others.18

Shared stories are a kind of “cultural toolkit”, providing us with moral frameworks, explanations and other story elements we can use for our own lives. This also explains why we are so strongly attracted to fiction. For a story to be valuable, it doesn’t have to be true. In fact, fictional stories are often attractive precisely because they aren’t as messy and unpredictable as real life. Or because they are richer, and thus add nuance and new perspectives to our own experience. Either way, fiction tends to make more sense to us than reality, and we use it to interpret events in the real world.

Beyond heroes

Not every sequence of events qualifies as a story. Stories must somehow be relevant to us as humans, and they must have a recognisable structure. Nearly every text on storytelling goes on to explain this using the Hero’s Journey. This story structure underlies many myths, popular stories and Hollywood blockbusters.19 It is attractive in part because it represents the significant human experience of a rite of passage, an event or ceremony that marks an important transition in someone’s life. We all recognise this as being important. Also, stories that adhere to the Hero’s Journey structure emphasise group values such as compassion (for “good guys”) and risking oneself to serve the community. And the struggle inherent in such stories engages our emotions and highlights a significant human goal: often we need to face fears and overcome obstacles in order to grow.

However, the popularity of the Hero’s Journey structure makes it easy to overlook that many stories don’t actually follow it.20 Also, focusing too much on structure risks overlooking other key aspects of stories, for instance that they are about goals and values, and about making sense of the world. Also, stories have a tone: they can be more positive or more negative. The importance of such aspects becomes clear when our stories fail to make sense of the world. For instance, people who express more positive life stories tend to score better on measures of wellbeing.21 They do experience difficulties, but see them as opportunities for growth. Conversely, anyone familiar with depression will recognise that the associated life narratives often have a negative tone. If you are depressed, you experience little control over your life. Long-term goals may be absent or feel irrelevant or unattainable. Much of what therapy does is to help re-frame such negative life stories in a more positive way. More importantly, recovery from depression often involves finding new long-term goals, or new ways to reach existing goals.

Mental versatility

We have seen that stories are central to our conscious experience, our wellbeing, our morality and to our social cohesion. We have also seen that our “thinking” takes many forms and involves many interacting processes, only some of which are conscious. All of these mental processes are highly functional, meaning that they are very good at performing certain tasks. We need automatic processes for efficiency. We require feelings and emotions to point out our needs, to distinguish “good” from “bad” and to motivate us. We need analytic thought to correct some of the errors and biases introduced by the other, more efficient processes, and to do long-term planning. And we use “story” or “narrative” to structure our experiences, our goals and values, and to share these with others. These are all aspects of “thinking”, and they are all important.22 But crucially, they all have their weak spots, and it helps to be aware of these.

The many pitfalls of thinking and feeling

In his discussion of “fast” vs. “slow” thinking, Daniel Kahneman emphasised that the unconscious processing of “System 1” is fast and efficient, but it can also be sloppy. The pioneering work of Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky spawned much research into cognitive bias, the many ways in which our thinking tends to deviate from “rationality”. Biases fall in a number of categories, which are nicely visualised in this overview (from Wikimedia):

While the notion of cognitive bias is only half a century old, people have long recognised that emotions and “gut feelings” are important, but can also be highly problematic if left unchecked. This has been pointed out by philosophers, sages and religious thinkers going back at least 2500 years. Notable examples include Buddhism, Stoicism, Taoism and Aristotelian ethics, all of which emphasise the importance of emotional awareness and emotional regulation. Contemporary research confirms this. Take for instance the huge 2022 review of psychotherapy methods by Stephen C. Hayes and collaborators. They found that when it comes to mental health, the single most important skill to develop is psychological flexibility. As Hayes explains, this entails being aware of your thoughts and feelings, and accepting them even when they are difficult or painful. It also involves using observed feelings to figure out your core values, and acting in accordance with these.23

Rational thinking can contribute to emotional regulation, and it is essential for correcting biases. However, reason by itself does not guarantee good outcomes. I already mentioned that analytical thought requires attention to details, which makes it difficult to apply to complex systems. But a far more common problem is that rational thinking allows us to come up with reasons for just about anything. Our big brains can easily cook up reasons for why we feel the way we do, and has no problems justifying biased thinking, far-fetched conspiracy theories and all kinds of immoral and even self-damaging opinions and behaviours. Also, analytical thinking doesn’t magically lead to objectivity, science or progress.

Rational thinking didn’t suddenly appear during the European Enlightenment. What did evolve was the particular social structure of science. As I discussed in an earlier article, the main social convention that emerged was the “iron rule”. This rule says that theories are only taken seriously in science if they match empirical observations.24 As anyone familiar with science knows, this doesn’t prevent the appearance of incorrect, incomplete or conflicting theories. However it does sufficiently constrain and coordinate theoretical thinking, so that incorrect explanations tend to be outcompeted or invalidated over the long term. In the short run, science is hard work, often messy and not always rewarding. Moreover, this way of thinking, working and communicating is very far removed from the lives and problems of most people. Science doesn’t come naturally to us. People generally prefer a good story to “scientific facts”, with all their nuances and complexities.

Stories work well for us because they combine and structure human feelings, problems, goals and values into a recognisable whole that can be easily copied and modified. This is a powerful ability that humans have, and that we’re naturally good at.25 Because stories are packages that contain facts, emotions and values, they can motivate people much more easily than “mere” factual information can. But the ability of stories to simplify and compress a complex reality into attractive packages is also dangerous. One problem is the risk of oversimplification: simple stories with a recognisable plot and characters (e.g. heroes vs. villains) can be more attractive than the messy complexities and uncertainties of real life. A related concern is that our shared stories can easily be captured by others.

Mind pirates

Because shared stories are attractive and can influence our goals, they can be used to direct our behaviour. Attempts to do so are easy to find: simply turn on a television or open YouTube or Instagram. Advertisements are basically very short stories that are designed to generate or tap into feelings, in order to influence our short-term goals. Marketing tries to persuade us to buy goods and services. Propaganda basically uses the same tricks to influence the values and behaviour of groups in society. This is no coincidence, as the psychological techniques used in modern marketing were originally adapted from 20th century war propaganda.26 Propaganda has been around as long as human group conflict, but mass media and the internet have made its distribution a lot easier. You need look no further than contemporary politics, conflicts and culture wars to see that shared stories are potent weapons for manipulating collective thinking and behaviour.

Luckily we are not mindless automatons, we have various mental, emotional and social defence mechanisms. Marketing and propaganda depend on scale, they can have significant social or economic impact only when large groups of people are involved. But as individuals we are not so easily manipulated into beliefs or behaviours that run counter to our core values. Also, we are used to being bombarded with conflicting stories, and our social environment has a strong influence on which narratives we accept. A healthy, supportive and diverse social environment isn’t just important for wellbeing, it can also help protect against problematic narratives. And emotional regulation and awareness are important here as well, because especially propaganda tends to target powerful “negative” emotions such as fear and rage.

Most of the mental “weak points” we examined can be ameliorated by being more aware of what’s going on in our mind. You can train yourself to be more aware of unconscious bias, unhelpful thoughts, corrosive feelings and oversimplified stories. You can also train others. If we want better decisions, it isn’t enough to have better information. We shouldn’t just aim to educate ourselves and others. We also need to build essential mental and emotional skills, such as self-awareness and being aware of stories.

Future fictions

We tell many stories about what happened in the past, both to ourselves and to others. But a unique aspect of stories is that they can be about the future. Stories about the future are fiction, by definition. But they shape our priorities and our expectations, and we’ve seen that they can strongly affect our wellbeing. Shared narratives about the future have a similar role for societies. They help us identify problems and set shared priorities. Also, if we change shared narratives, we can shift group behaviour and norms in the long run, for better or for worse. Abolishing slavery, giving voting rights to workers and women and recognising human rights were all attained through slowly shifting social norms. Shared stories were important in this. Perhaps less positively, the “big stories” of religion, socialism and capitalism have had a huge influence on human history, and they still shape how we think about the future.

In my first article I discussed three common types of stories about sustainability. What I called “ecopessimist” stories have a negative tone, while “ecomodernist” and “neo-romantic” stories are more optimistic (but emphasise different values). In my next article I will examine two broad classes of stories about the future: the narratives of Progress and Decline. We will see that fictional stories about the future have very important consequences for what we as humans do in the present. And what we do in the present does eventually determine the future, just not always in the way our stories predict.

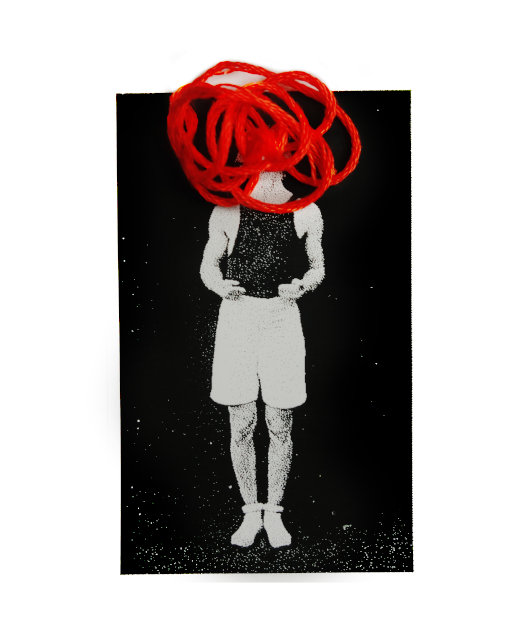

“Red thread” images by Io Cooman. Cognitive bias codex by John Manoogian III and TilmannR (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Do you want to be notified when future articles in this series are published? Subscribe to my Substack, or follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky or Twitter/X. You can also subscribe to our Atom-feed.

Further reading

Robert Sapolsky. Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Publishing Group, 2017.

If you’re going to read only one book about neuroscience, psychology and human behaviour, you should probably read this one. With around 700 pages (plus many notes) it isn’t exactly a short read. But neuroscientist and biologist Robert Sapolsky does an excellent job at showing that there are few things as complex as human behaviour. We cannot point to any single factor that determines a given behaviour. Instead all human behaviour is determined by many factors, including our neurophysiology, hormones, all kinds of unconscious influences, our personal history, our age, our social environment, our culture and society, our genes and our evolutionary history. Sapolsky then goes on to show how these diverse factors interact to shape things such as social identities and ingroup/outgroup dynamics, socioeconomic hierarchies, morality, justice, group violence and peaceful coexistence. He ends the book with two general observations (spoiler alert!). First, it’s complicated, but that’s no excuse not to try and improve things. Second, you don’t have to choose between science and compassion, you can have both. Sapolsky gave a TED talk about some of the ideas discussed in the book.

Stephen Macknik, Susana Martinez-Conde and Sandra Blakeslee. Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about Our Brains. Profile Books, 2012.

Somewhat more accessible (and much shorter) than Sapolsky’s tome, this excellent book by the research and magician couple Stephen Macknik and Susana Martinez-Conde approaches neuroscience from the perspective of magicians and their audience. As Susana also explains in this interview, your brain doesn’t so much observe as construct the world “out there”, and it often gets things wrong. The book discusses the neuroscience behind magic tricks and visual illusions. Many magic tricks take advantage of the limitations of conscious attention and memory, the “sloppy” shortcuts your brain takes for speed and efficiency, and various adaptive mechanisms that allow us to function in a wide range of environmental conditions (e.g. both by day and by night). Our visual system mostly has pretty terrible resolution, and it relies to a large extent on signal processing, memory and prediction. Therefore we don’t consciously see many of the things that happen right in front of our eyes. What we see is merely our best guess of what is out there. Also the way in which we reconstruct cause and effect is quite sensitive to manipulation, because we tend to come up with explanations and justifications “after the fact”. Even if our explanations are wrong, we still consider them to be “truth”—a fact that can easily be exploited by magicians, mentalists, con men and propagandists.

Many of the concepts and examples discussed in the book are also discussed by Stephen and Susana in this presentation at the 2013 GoldLab symposium.

Steven A. Sloman and Philip Fernbach. The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone. Macmillan, 2017.

Cognitive scientists Sloman and Fernbach point out that we know a lot less than we think. All of us overestimate our individual skill and knowledge, especially outside our particular fields of expertise. We generally deal with complexity by ignoring it. As we grow up, we stop asking questions about the way things really work and assume that we know quite well. This illusion of knowledge acts as a kind of self-protection mechanism, it supports our self-narratives and allows us to make decisions under grossly incomplete knowledge, while still feeling we are being rational.

According to Sloman and Fernbach, the purpose of “thought” is to process information in order to select among appropriate actions. This requires predicting the outcome of actions, and thus understanding cause and effect to some extent. Humans are naturally good at causal reasoning, thinking in terms of causes, effects and influential factors, mostly based on “mental simulations”. True “logical thinking” is much more difficult for us, as is diagnostically reasoning backward from effect to cause. Moreover, we think in terms of causal models, not in terms of “facts”, and our causal knowledge is mostly shallow and based on metaphors and stories.

We use storytelling to share causal information and analyses, because the human mind is much more than the brain of an individual person. Knowledge isn’t just stored in the neural networks of our brain, but also in the world, our body and especially in other people. Solving complex problems requires many minds, with complementary skill sets and a division of cognitive labour. True intelligence in the practical sense is not a property of individuals, it is a property of teams. This is often overlooked in individualist cultures, which tend to focus on single “heroes” as the main causal factor in collective success.

Due to the collective nature of intelligence, information actually has very little effect on our beliefs, while our community tends to have a big effect. We can easily generate reasons for our beliefs, or copy these from others. Even worse, many of our strong opinions are determined by “sacred” values, rather than by causal reasoning on how preferred outcomes may be obtained. In other words, strong value-based moral or political positions don’t even require reasons, and they tend to be resistant to the exposure of explanatory ignorance. This helps explain why “facts” matter a lot less than our social environment.

Certainty and ideological purity are dangerous. The first steps in making better decisions are therefore to allow doubt, to question our beliefs and to learn about our ignorance. For effective problem solving, we need to know what we don’t know, so we can go in search of others who can complement our ignorance with their skills and knowledge. Also we should realise that people never make decisions on their own. All decisions are to some extent communal: they are influenced by other people, and they can in turn influence other people.

Some of the ideas in this book are discussed with the authors in the Leeds Business Insights Podcast series 1 episode 7 and the Here We Are Podcast episode 358. Philip Fernbach also talks about this in his 2017 TEDx talk.

Mark Solms. The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. Profile Books, 2021.

https://profilebooks.com/work/the-hidden-spring

In this very impressive book, the neuroscientist and psychotherapist Mark Solms sets out the theory that consciousness is a much more fundamental brain function than was assumed by 20th century neuroscience. Mainstream theory assumed for a long time that consciousness must arise in the relatively “new” cortical areas of the brain, which are significantly enlarged in humans. Solms builds on the work of Jaak Panksepp, Antonio Damasio, Bjorn Merker and others, to show that consciousness might instead be generated in the upper brain stem, which is much older. Consciousness in their view is fundamentally about feelings, which indicate how well or badly you are doing in life. This is important for survival, because feelings indicate and prioritise needs. Many of our responses are automatic, but in cases where an automatic response does not suffice, conscious feelings are generated as an “error signal”. This also allows us to respond consciously, which is much more flexible than automatic behaviour, and can incorporate more and richer sources of information. In other words, the function of consciousness is to allow us to act on feelings. This gives us some degree of agency, it enhances learning and it supports survival in unpredictable contexts. In this view, neither consciousness nor feeling is unique to humans or higher mammals. Consciousness may be a feature of all animals with a sufficiently complex neural network, a position also promoted by Anil Seth in Being You and Antonio Damasio in Feeling and Knowing (both of which I can recommend as well). Humans may not be special due to consciousness or feeling, but we do have a number of “special features”, including symbolic language and social feelings. Language allows us to label, combine and transmit perceptions, categories and even abstract concepts, making them “thinkable”. This extends our consciousness far beyond the domain of acting on feelings. Verbal labels and stories also extend the concept of learning, beyond the laborious business of acquiring personal experience. Thanks to language, we can build up experience and “thinkable objects” across individuals, societies and generations.

Finally, Solms discusses how our internal predictive models may work, following Karl Friston’s free energy principle. This formal theory basically states that a brain tries to minimise surprise and maximise the evidence for its model of the world. This can be done by either changing the internal model (learning) or by changing the outside environment (acting). Anil Seth also discusses this subject in his book Being You.

Some of the ideas in The Hidden Spring are discussed by Solms in the Machine Learning Street Talk podcast and in a Royal Institution science video.

Ethan Kross. Shift: Managing Your Emotions–So They Don’t Manage You. Random House, 2025.

https://www.ethankross.com/books/shift

Ethan Kross is a researcher who specialises on emotional regulation. He discusses the function and importance of emotions, as well as the many problems that can result from strong emotions or our attempts to suppress them. He then gives a number of strategies to manage emotion in healthy ways. Kross also talks about this in the Rich Roll Podcast episode 894 and on Dan Harris’ 10% Happier podcast.

Michael Murray (2015) ‘Narrative Psychology’, in Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. SAGE, p. 85.

Ruthellen Josselson and Brent Hopkins. (2015) ‘Narrative Psychology and Life Stories’, in The Wiley Handbook of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 217–233. (preview)

János László. (2008) The Science of Stories: An Introduction to Narrative Psychology. Routledge, pp. 1-6.

These three book chapters offer a decent introduction to the field of narrative psychology, which arose in the 1970s and 1980s based on the work of scholars such as Theodore R. Sarbin, Jerome Bruner, Paul Ricœur, Dan P. McAdams, Charles Taylor, David Carr and others. Sarbin contrasted the machine metaphor that, he argued, underlay much of mainstream psychology with that of the narrative metaphor. In giving accounts of ourselves or of others, we are guided by narrative plots, and we render events into a story. Ricoeur argued (in his 1984 book Time and Narrative) that we need to create narratives to bring order and meaning to a constantly changing world. Carr argued that human experience inherently has a narrative or story-telling character. McAdams argues that we seek to provide our scattered and often confusing experiences with a sense of coherence by arranging the episodes of our lives into stories, which are in essence “personal myths”. And Bruner distinguished “narrative modes of knowing” (in which the lived experience is central) from “paradigmatic knowing” (which is about relationships among measurable variables).

Annie Duke. How to Decide: Simple Tools for Making Better Choices. Penguin Publishing Group, 2020.

https://www.annieduke.com/books

Consultant and (former) professional poker player Annie Duke shows that biases and self narratives are almost guaranteed to distort our attempts at making “rational” decisions. Decision making involves predicting the future to some extent, which is always subjective and requires both imagination and an accurate feeling for probabilities and uncertainties. Higher quality decisions can be obtained when we reduce bias and maximise learning based on all the useful information we can get. Imagination and “mental time travel” are important in anticipating possible obstacles, while “positive thinking” can cause problems because it hides potential problems while boosting confidence. Actively searching for dissenting opinions and “outside views” is essential to reduce groupthink, rationalisation and overconfidence. Duke discusses many useful techniques, and she shows how hard it is to engage in truly rational thinking. The role of chance is much bigger than we think, the effect of our decisions tends to be limited and there is much more we don’t know than what we do know. We can and should make higher quality decisions, but it is hard work that requires a lot of self-discipline. Academic readers may notice that many of the techniques described by Duke are functionally quite similar to Bayesian approximation and are operationalised in one way or another in the scientific method and the social structures of academia, as described by philosopher Michael Strevens.

Duke also discusses her ideas on Lenny’s Podcast, in the Modern Wisdom Podcast episode 233 and in the Rational Reminder Podcast episode 120. The book’s main points are summarised in this short Lozeron Academy video.

Daniel Kahneman. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

In this bestseller, Daniel Kahneman introduced the subject of cognitive bias to a broader public. Most of the examples in the book are based on the pioneering work of Kahneman and Amos Tversky in behavioral economics.

Robert A. Burton. On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not. St. Martin’s Press, 2008.

Bruce Hood. The Self Illusion: How the Social Brain Creates Identity. Oxford University Press, 2012.

John Bargh. Before You Know It: The Unconscious Reasons We Do What We Do. Simon and Schuster, 2017.

These accessible books further discuss several interesting aspects of neuroscience. Neurologist Robert Burton argues that certainty is a feeling, rather than something that is based on careful deliberation and facts. This “feeling of knowing” is independent of actual knowledge or the products of reason, and it forms the basis of mystical revelations, religious experience and many forms of overconfidence. You can also listen to an interview with the author on EconTalk.

In The Self Illusion (and in this online lecture), psychologist Bruce Hood argues that reality as we perceive it is not something that objectively exists, but something that our brains construct from moment to moment. Moreover, what we experience as the “self” is also a mental illusion. Our experience of being a “self” emerges across childhood, as the brain constructs story-models from our experience, which strongly interact with the influences of other people. The feeling of being a “self” is important, however, because it provides us with a focal point to hang experiences together, both in the present and integrated over our lifetime.

Finally, social psychologist John Bargh offers an overview of the many unconscious and automatic aspects of cognition, many of which are highly functional. He also discusses some of the ways in which our environment ends up influencing our thoughts, feelings and decisions. Many subjects from the book are also discussed by Bargh in this lecture.

Will Storr. The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better. Abrams, 2020.

Kendall Haven. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story. Bloomsbury Academic, 2007.

Jonathan Gottschall. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Jonathan Gottschall. The Story Paradox: How Our Love of Storytelling Builds Societies and Tears them Down. Hachette UK, 2021.

These four books offer a nice introduction to many aspects of stories, including some of the underlying psychology and neuroscience, important story elements, the social functions of story and the negative side-effects of simplified stories, especially in the context of social identities and between-group violence. These books are very readable, but the downside is that much of this writing does tend to overstate the impact of story. Yes, story is important because it structures our experience, integrates with our emotions and it can be transferred to other people. But it’s good to keep in mind that many other factors also influence our wellbeing and our behaviour, as Robert Sapolsky nicely shows in his book Behave.

Paul B. Armstrong. Stories and the Brain: The Neuroscience of Narrative. JHU Press, 2021.

Nigel Hunt. Applied Narrative Psychology. Cambridge University Press, 2023. (preview)

János László. The Science of Stories: An Introduction to Narrative Psychology. Routledge, 2008.

In the first of these three academic books, Paul Armstrong contemplates the neural basis of narratives, with a focus on fictional stories (e.g. literature and film). He discusses how our brain links perceived effects to their perceived causes, and how we use this to transform our experience into familiar narrative patterns. The narratives we construct and recognise are strongly influenced by culture, but our narratives can also end up influencing culture. Collectively, we construct and use narratives to make sense of the world. Unfortunately, some of Armstrong’s conclusions seem rather speculative, and his writing can be a bit abstruse.

The other two books offer an in-depth exploration of the applications of narrative techniques in psychology, including life interviews and the use of narrative methods in therapy.

Dylan Evans. Emotion: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Simon Blackburn. Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2021.

The short introduction to emotion discusses, among other things, the evolution and function of emotions and their biological basis, the science of happiness, and the role that emotions play in memory and decision-making.

Simon Blackburn’s short introduction to ethics nicely illustrates how we collectively construct stories about which things are “good” and which things are “bad”. Blackburn points out that such stories are important in guiding our sense of morality, but that we need to be aware of their limitations and assumptions as well.

Footnotes

-

from the perspective of neuroscience, all forms of thinking involve processes that we could consider “irrational”

Technically, we should probably call some of these processes arational rather than irrational. An arational process has nothing to do with rational thinking. An irrational one does, but it does not fulfill the standards of rationality. Processes involved in, say, motor function have relatively little to do with rational thinking (although we do engage motor circuits in mental simulation). But mental processes that lead to cognitive bias can clearly cause irrational outcomes. Such “irrational” processes are also responsible for intuition and “gut feeling”. Interestingly, these forms of mental (and bodily) processing can sometimes yield better outcomes than rational processing would do. This applies mostly to rapid decisions or dealing with high complexity (which includes many social situations). Our irrational (or arational) intuition is relatively well-equipped to handle such situations, although good outcomes are certainly not guaranteed, and experience matters a lot in such cases. ↩ -

Even our conscious, “rational” thinking is not necessarily based on empirical evidence or on strictly logical argumentation.

Science and philosophy are hard, precisely because strict logical thinking doesn’t come naturally to us, and finding and verifying proper empirical support is very time-consuming (if we find it at all). Much of our day-to-day “rational” thinking actually isn’t logical deduction, induction or abduction. Instead, it is based on mental simulations of how causes lead to effects. This type of causal reasoning based on internal simulation seems to be something we are good at, and it may well form the basis of imagination and storytelling. Unfortunately these same faculties also allow us to rationalise and confabulate. We can easily come up with “rational” explanations that have little to do with logical reasoning and are not well-supported by empirical evidence. Or we selectively look for evidence supporting our existing beliefs, while ignoring counter-evidence. This behaviour, known as confirmation bias, is almost impossible to avoid, which is why science requires peer review and strict adherence to empirical observation in order to function well.

However, often we feel we are certain of things, even without engaging in much rational thinking or having any empirical support. Cognitive scientists Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach describe many examples of this in their book The Knowledge Illusion (and in a TEDx talk on the same subject). A well-known example of this is the Dunning-Kruger effect: if you know little about a given subject, you will tend to overestimate your competence in that field. And in his book On Being Certain, neurologist Robert Burton argues that certainty is a feeling, rather than something that is based on careful deliberation or facts. He calls this “the feeling of knowing”. It is the feeling we get upon sudden insight, and the driving force that keeps us looking for evidence to support things we “know to be true”. It also forms the basis of mystical revelations, religious experience and many forms of overconfidence.

Rationalisation and the illusion of knowledge may seem like “bugs” in our mental system, from the perspective of rationality. But these mental features are actually quite functional in daily life, acting as a kind of self-protection mechanism in a complex and unpredictable environment. The various forms of self-confidence allow us to make decisions under grossly incomplete knowledge, while still feeling we are being rational. ↩ -

However, having no inner voice or visuals doesn’t mean that you have no thoughts. It just means that you aren’t conscious of what your thoughts are.

This is called unsymbolised thinking. In a 2023 article in the New Yorker, Joshua Rothman describes what this is like. He has fully formed thoughts, but they appear in his consciousness only when he is talking or writing. ↩ -

Our conscious thoughts often revolve around our goals and around feelings

I use “feeling” in the neurological sense of the word: as something we consciously feel, or more formally as “a self-contained phenomenal experience”. Feelings can be generated by sensations, by needs or by emotions (and in fact, all three are closely connected and can overlap to some extent). Sensations can be internal to our body (interoceptive) or about external things (exteroceptive). An emotion is at least in part a bodily response to a situation, a memory or an anticipation. These bodily responses (e.g. an increased heart rate and other effects of stress hormones) lead to internal sensations, which we then become aware of as feelings. It is therefore not surprising that we tend to associate feelings with emotions, and that we associate the heart with strong emotion. Many emotions trigger changes in heart rate and circulatory patterns, and we consciously experience such effects as “feelings”.

Feelings and emotions are not the same, although they are often used interchangeably in common speech. Emotion does lead to feeling, but feeling is a more general term. Pain and hunger are feelings, but they are not emotions. For a more detailed discussion, check out the work of Antonio Damasio, e.g. as summarised in his short book Feeling and Knowing. ↩↩ -

Even our unconscious thought is driven strongly by goals.

The fact that many of our decisions are unconscious and automatic is often used to argue against the existence of free will. In his excellent book Free Agents, neurobiologist and genetics researcher Kevin J. Mitchell argues that this is due to an overly narrow (and human-centric) definition of “free will”. Organisms, ranging from microbes to roundworms to humans, all have goals that are related to survival and that drive flexible behaviour in unpredictable environments. In order to allow for flexible responses, organisms build internal predictive models of their world, which are embodied in neural and molecular networks and other physiological structures. These models allow living beings to do things, to act as agents that can cause things to happen, driven by their internal predictions and goals. Even if much of our mental processing isn’t conscious, we are still causal agents in this sense, and we act according to internal goals. These goals can be set or shifted consciously at least to some extent, so they offer a way to influence our unconscious and automatic mental processes. ↩ -

Constructing a full and accurate model of our surroundings would be way too costly, so our brain aims for something that is “good enough”.

For instance, rather than recognise, track and learn about every individual object or person around us, we put things and people into broad categories about which we may hold general assumptions. And our sensory system is mostly sensitive to change, it ignores signals that are always present (e.g. we don’t see our nose, even though it is in our visual field). In general, our brain suppresses the processing of data that it deems predictable and thus uninformative. When we feel our situation is sufficiently familiar, we unconsciously draw many of our “perceptions” from memory. This generates a “prediction of the present” that is largely incomplete and full of assumptions, but usually works well enough for us. However, magicians exploit the fact that we actually perceive only very little of our surroundings. This is explained very nicely by Stephen Macknik, Susana Martinez-Conde and Sandra Blakeslee in their book Sleights of Mind.

The fast processing of System 1 that Daniel Kahneman describes in Thinking, Fast and Slow is another example of the widespread use of mental shortcuts by our brain and our body. ↩ -

Two situations can powerfully grab our attention. One is surprise, which happens if reality does not seem to match the predictions generated by our brain. This requires that we pay more attention to details and figure out what’s going on.

So-called Bayesian brain theories postulate that the brain tries to minimise prediction error. One of the strongest proponents of this approach is Karl Friston, and readable descriptions of the underlying ideas are given by Anil Seth in his book Being You and by Mark Solms in The Hidden Spring. Karl Friston’s formal approach basically states that a brain tries to minimise surprise and maximise the evidence for its model of the world. An organism can do this by either changing its internal model (i.e. by paying attention and learning) or by changing the outside environment (i.e. by acting on the world). Friston talks about this on the Big Biology Podcast episode 70. ↩ -

There is a fish in the percolator […] Should I still drink the coffee?

Also, what does David Lynch have to do with any of this? ↩ -

We also have feelings about the external environment. These are a bit more complicated (because they are linked to emotions)

As pointed out in an earlier footnote4, feelings and emotions are different things. Emotions are (at least in part) coordinated physiological responses to things happening in our environment (or to past events that we recall from memory, or to future situations that we anticipate). Feelings are the aspects of emotional responses that we consciously feel. Emotions are thus feelings and responses in one single package, and they can go far beyond the kind of “simple” bodily responses that occur in, say, rage or lust. Complex emotions may co-opt some of the neural circuitry of more “primitive” ones (e.g. those for pain). But complex emotions are hybrid processes that can involve various interacting emotional circuits, learnt behaviour, our reward system and various kinds of “higher-level” mental processing. Some examples of this are discussed by Mark Solms in chapter 5 of his book The Hidden Spring and by Robert Sapolsky in chapter 7 of Behave.

Emotions are about our needs relative to the external environment, which in a social species like humans largely consists of other humans. Because our environment isn’t static, the regulation of emotions requires some degree of learning about things in our direct environment, especially the behaviour of other people close to us. This learning involves our reward system, which predicts rewards as well as (to some extent) punishments. These systems can automatically regulate emotions and behaviours up or down, depending on our learnt predictions. This is necessary, because we need to learn when we can or should engage emotional responses such as fear, rage or lust, and when to suppress them. Unregulated emotions are very problematic for social species such as ourselves. However, quite a few things can go wrong in this learning process. For instance, fear conditioning is very rapid and can happen early in life, before we lay down conscious memories. We can thus be afraid of things without knowing why, due to something that happened in our early childhood. Also, problems with attachment to caregivers (e.g. separation anxiety) or other forms of chronic stress early in life can have long-lasting and significant effects later in life. Bad outcomes may include anxiety, depression and other mood disorders, as well as unhealthy attachment and addiction.

Emotions may be largely automatic (we have little conscious control over them), but they strongly influence our conscious, voluntary behaviour, especially under conditions of uncertainty. They are highly functional for survival and social coordination, as long as their regulation does not go awry. Despite the fact that emotional responses are mostly automatic, we can learn to regulate them in healthy ways, and we can correct unhealthy regulation later in life. Examples of how we can do this are given by Ethan Kross in his book Shift. ↩ -

The way feelings and emotions work seems to be similar across many animal species.

The basic way in which feelings work at the neurological and hormonal level seems to be similar for all mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and other animals with a backbone (vertebrates). At least all mammals also seem to share a set of basic emotional states, which relate to things happening in the immediate external environment, and which include fear, rage, lust, play, care and panic/grief. This list of seven basic emotions in mammals (and certain birds) was proposed by Jaak Panksepp, based on animal experiments. They are described in Panksepp (2005, PDF) and in his book Affective Neuroscience (1998). Different emotional classification schemes have been proposed by other authors, mostly based on human studies. Note that the various theories on how emotions work are generally not mutually exclusive, they mostly differ in the relative importance they assign to various processes. ↩ -

In essence, a story can be thought of as a coherent ordering of selected information in time. […] Stories owe their familiar shapes to recognisable patterns of events that we call plots.

See e.g. Mar (2004) and Crossley (2002). Unfortunately there is no commonly agreed-upon definition of terms such as story and narrative. In colloquial usage, story and narrative are more or less the same thing, but various authors, fields and dictionaries define them in different ways. Unfortunately many of these definitions are incompatible with each other and sometimes even with common human experience, as the author Kendal Haven points out in his book Story Proof.

I will treat “story” and “narrative” as more or less equivalent, and I will mostly use these terms in a sense suggested by the philosopher Paul Ricoeur. For Ricoeur, narrative refers to how humans experience time, the ways in which we understand future potentialities and mentally organise our sense of the past (see Rhodes, 2016). Narrative in this sense is a fundamental mental construct, a way of organising time and experience and relating it to meaning. According to Ricoeur, humans “narrativise” their past, and we carry out “emplotment”: we draw together disparate past events into a meaningful whole, by establishing causal and meaningful connections between them. In this way, the past is connected to the present, to our values and to future goals and possibilities. Familiar patterns are established (in the form of plots), and the future, in turn, is seen as a set of potential narratives. ↩ -

we experience our memories as a kind of coherent story, often with a plot that revolves around our intentions, or those of other people.

When we think or talk about other people, we try to infer their intentions, but of course we cannot actually know for certain what their intentions are. We only have direct access to our own intentions, and even these are usually rationalisations, rather than an accurate reflection of the many factors that actually determine our behaviour. Therefore we have a tendency to ascribe good intentions to ourselves (rationalisation), and bad intentions to others (hostile attribution bias). The latter is a major driver of aggression toward other people. In general, we are quick to assume intentionality, even in (the rather common) cases when behaviour is unintentional. This is known as intentionality bias, and it helps explain why we blame others so easily, and why we are susceptible to conspiracy theories. Robert Sapolsky discusses the causes and consequences of these biases at length in his excellent book Behave, especially in chapter 13 (on moral behaviour). ↩ -

This doesn’t make us hypocrites, it just makes us human.

A hypocrite is a person who professes beliefs and opinions that he or she does not hold in order to conceal his or her real feelings or motives. This is not what happens if you hold conflicting values. However, in some sense we do conceal such inconsistencies from ourselves, and therefore also from others. This is not an intentional act, it is a form of mental self-protection. ↩ -

We have strong feelings about fairness and what constitutes “right” or “wrong”.

In general, feelings are usually not neutral, they tend to have a valence. We experience feelings as positive or negative, although this does depend on context, and we can also feel ambiguity or conflict. Affective evaluation, judging something to be good or bad, is probably a fairly basic feature of conscious feeling. All animals (and even many single-celled organisms) seem to judge things roughly along a basic affective axis of good (approach) vs. bad (avoid) (although, of course, it’s complicated). Because we humans are an extremely social species, we have extended our evaluation of “good vs. bad” to distinguish “right” from “wrong” behaviour in the context of social groups. This is linked to the ways in which we construct social identities (think “us vs. them”, in which “us” is more often seen as “good”). Also, humans are unique in that we can come up with reasons to judge actions and values. ↩ -

We are not isolated individuals with purely independent goals and feelings. Instead we are more like actors, engaged in various plots in a world of others.

See Josselson & Hopkins (2015). ↩ -

Nearly every text on storytelling goes on to explain this using the Hero’s Journey. This story structure underlies many myths, popular stories and Hollywood blockbusters.

In the Hero’s Journey, the main character has to leave their community or home to face a series of trials. The hero eventually returns transformed, with a new understanding. The story arc typically follows a three-act structure. The Hero’s Journey story structure (or “monomyth”) was popularised by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which subsequently had a big influence on the work of filmmakers such as George Lucas (e.g. in his Star Wars films) and on the approach taken by many (especially Western) storytellers. People have since advocated the use of similar story structures in just about any type of storytelling, from fiction to marketing and even science communication. ↩ -

the popularity of the Hero’s Journey structure makes it easy to overlook that many stories don’t actually follow it.

Joseph Cambell’s “one size fits all” interpretation of mythology has been widely criticised by folklorists, artists and activists. And Wikipedia’s list of story structures does not even mention the Hero’s Journey: There exists a much bigger diversity when it comes to the structure of actual stories, especially outside Western pop culture and foundational myths. ↩ -

people who express more positive life stories tend to score better on measures of wellbeing.

See Baerger & McAdams (1999), and also Josselson & Hopkins (2015), Murray (2015, PDF) and McAdams (2006). For both fiction and their own life stories, most people seem to prefer positive stories over negative ones. There should be struggle of course, but in a positive story the obstacles are eventually overcome. ↩ -

These are all aspects of “thinking”, and they are all important.

We can see the importance of various mental processes when they fail to operate, for instance when brain damage occurs. Regardless of whether a region is old or new (from an evolutionary perspective), damage to a normally functioning brain always leads to worse outcomes. For instance, disabling emotional evaluation doesn’t generate some kind of rational superhuman. Rather, loss of emotional “gut feeling” generally leads to very bad decisions, and can even result in a complete loss of motivation, as pointed out by Robert Sapolsky in Behave. And damage to other areas involved in narrative processing (e.g. related to temporal organisation, memory, mental simulation, affective tone, etc.) can cause various kinds of “dysnarrativia”, problematic states of narrative impairment, examples of which are described by Young & Saver (2001, PDF). They conclude that “brain injured individuals may lose their linguistic, mathematic, syllogistic, visuospatial, amnestic, or kinesthetic competencies and still be recognizably the same persons. Individuals who have lost the ability to construct narrative, however, have lost their selves.”

Evolutionarily more recent brain areas include the prefrontal cortex, which is greatly expanded in mammals, especially in humans (and other primates). One of its major functions is to suppress and expand on automatic behaviour. But the prefrontal cortex would not be able to perform these functions without the older brain systems: it regulates and supplements older systems, rather than replacing them. In fact, as described by Mark Solms in his book The Hidden Spring, consciousness may well reside in these older, more fundamental brain systems. This implies that consciousness is probably not unique to humans, mammals or even vertebrates. And it also means that feelings are central to consciousness, and they are therefore fundamental rather than optional. The newer features supplied to us by evolution include the ability to ignore or reflect on feelings, and to override or otherwise regulate emotions and automatic responses, so that they do not end up fully governing our behaviour. ↩ -

Take for instance the huge 2022 review of psychotherapy methods by Stephen C. Hayes and collaborators. They found that when it comes to mental health, the single most important skill to develop is psychological flexibility.

After studying 281 results (from an initial set of nearly 55000 studies), Hayes et al. found that one single set of skills proved far more commonly effective than anything else. According to Hayes in his blog, this skill set “was more frequently found than self-esteem; support from friends, family, or your therapist; and even whether or not you have negative, dysfunctional thoughts. The most common pathway of change was your psychological flexibility and mindfulness skills.” Hayes goes on to explain: “The first pillar of psychological flexibility is awareness. This means noticing what happens in the present moment: What thoughts show up? Which feelings? […] The second pillar of psychological flexibility is openness. This means allowing difficult thoughts and painful feelings – exactly as they are […] openness is about dropping the internal fight, allowing thoughts and feelings to be what they are – merely thoughts and feelings – without them needing to control you. […] The third and final pillar of psychological flexibility is valued engagement. This means knowing what matters to you, and taking steps in this direction. It involves being in contact with your goals – objectives you want to reach or achieve – and your values – those personal qualities you choose to manifest and be guided by, regardless of a specific outcome. These matters need to be freely chosen, rather than being forced on by others, or mindlessly followed out of custom. But once you have clarity about what matters, you can take action to build sustainable habits that make your life more about what gives it meaning.”

The skill set Hayes describes is similar to some of the core teachings of Buddhism and several other traditional philosophies (in the sense of acknowledging the value of awareness and accepting difficult thoughts). Also, these results resonate with writings of several popular authors such as Jonathan Haidt, Sam Harris, Brené Brown, Matthieu Ricard, Mark Manson, Gabor Maté, Adam Grant and others. ↩ -

the main social convention that emerged was the “iron rule”. This rule says that theories are only taken seriously in science if they match empirical observations.

This interpretation of science is based on the work of philosopher Michael Strevens, which he describes in his book The Knowledge Machine, in the paper Science Is Irrational—and a Good Thing, Too and on the Jim Rutt Show podcast, episode 106. ↩ -

Stories work well for us because they combine and structure human feelings, problems, goals and values into a recognisable whole that can be easily copied and modified. This is a powerful ability that humans have, and that we’re naturally good at.

The mental skills involved with narrative thinking and cause and effect prediction do however take some time to develop. Children learn to understand and tell stories at a young age, but before age five the temporal structure of their stories tends to be all over the place, and their sense of causality generally has little to do with reality. ↩ -

the psychological techniques used in modern marketing were originally adapted from 20th century war propaganda.

During the First World War, the US Committee on Public Information (CPI for short) was created to influence public opinion to support the American war effort, using recent insights into mass psychology. The propaganda campaigns created by the CPI proved quite effective, and US propaganda techniques were subsequently studied by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, to inspire the propaganda efforts of Nazi Germany. Moreover, one of the CPI members, Edward Bernays, realised that propaganda techniques based on group psychology could also be employed in peacetime. In the 1920s, Bernays published several books and papers on this subject, including Crystallizing Public Opinion, Propaganda and Manipulating Public Opinion, thereby kickstarting the field of public relations (PR). Bernays believed that the “masses” were not very smart, and therefore that their minds can and should be manipulated by the capable few. Several of his successful accomplishments were rather questionable by today’s moral standards, including the Torches of Freedom campaign, designed to boost tobacco sales by encouraging women to smoke cigarettes. ↩