Looking for Better Stories on Sustainability

Reading time: ca. 18-25 minutes.

Too long? Read the 5 minute summary instead!

This article has been be published on https://lvzon.substack.com and Medium, and is also available as PDF or ebook (EPUB and Kindle) for offline reading. You can also listen to a narrated version:

By Levien van Zon

As a lover of books, I enjoy going into bookshops and libraries. I love to check out new releases on all kinds of subjects. But when it comes to one of my main interests, sustainability, I am often disappointed by the writings on offer. There are many excellent and important books on all aspects of sustainability. Yet, something always feels wrong. It feels as if we’re a bit stuck. Half of the stories I see seem too optimistic, and the other half too pessimistic. If we are moving forward at all, it’s only very haltingly, at least when it comes to important collective insights. The dominant stories on how humanity should proceed all seem to be somewhat broken. And more crucially, they contradict each other in important ways.

Modernists, romantics and pessimists

There exists quite a large diversity in thinking and writing on sustainability. Attempts at categorisation are often somewhat arbitrary. Nonetheless, let’s look at one particular way of categorising some of the major points of view on sustainability. One important way of thinking treats sustainability as mostly a set of technical or behavioural problems. In this view, technology X or Y or certain small changes in our behaviour will fix everything. We’ll call this the “ecomodernist” point of view. Then there are ideas on how everything is connected and on how modernity has messed things up. These usually suggest that we should put more trust in nature and in small communities, and less in technology and in human institutions. We can think of this as the “antimodernist” or “neo-romantic” point of view. Finally, there are quite a few stories on how we’re all doomed because of climate change, and on how only drastic and immediate action can keep humanity from going extinct soon. We’ll call this “ecopessimism”.

Usually we choose a point of view based on our existing beliefs and our preferences. If you want to believe that technology can solve most of our problems, you will probably prefer an “ecomodernist” view. Probably you will also believe additional things, which are connected to this. For instance: “progress” is a very powerful idea, and economic growth can help stabilise societies and drive innovation, as long as the negative side effects of economic activity can be kept in check. There is probably some merit to these ideas. However, you may also be overly optimistic about the future and the things that technology can do. And you may underestimate the myriad ways in which the complexities of the real world may sabotage even the best-laid plans and the most advanced technologies.

If you deem nature to be superior to anything that we humans tend to come up with, you will probably be partial to “neo-romanticism”. You may share my opinion that nature and long-standing cultural traditions aren’t “backward”. Rather, looking at natural evolution and traditional culture can be very useful, as this may provide us with robust, time-tested solutions to some of our modern problems. However, you may also presume that everything that is natural tends to be “good”. And even if you don’t, you may assign agency and purpose to nature in ways that don’t match our current understanding of how natural processes operate.

Finally, if you believe that humankind is basically digging its own grave, you will probably tend toward “ecopessimism”. You will recognise that infinite growth is impossible given finite resources, that technology tends to have negative side effects and that both of these can eventually destabilise societies. Indeed, climate change poses a serious challenge to both human and natural systems. But focusing too much on fears of collapse is probably unhelpful. You may underestimate the resilience of both natural and social systems, and their capacity to adapt when put under pressure. Moreover you will likely experience a constant feeling of urgency, and many of your expectations for the future will be built on fear. This may lead to anxiety and depression.

People like Bill Gates, as well as many economists, engineers, politicians and CEOs tend towards the ecomodernist perspective, claiming that the combination of technology and “green” economic growth is the way forward. People who put more trust in nature, community or spirituality often lean towards neo-romanticism. They propose that a sustainable future requires a “holistic” worldview, and local, small-scale and often low-tech solutions. This view is common in various “alternative” subcultures. It is also found in the “postmodern” discourse that is currently prevalent in much of the arts and humanities. And an example of ecopessimism can be found in climate activist movements such as Extinction Rebellion, that push for drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions now, to prevent complete climate collapse.

Wizard, prophet or both?

I’m oversimplifying. It is true that we tend to subscribe to viewpoints that match our existing beliefs and preferences. We also listen more favourably to ideas and opinions that are common in the social groups that we belong to. But things aren’t as rigid as they seem. Humans are very good at believing multiple things at the same time, even if these are not mutually consistent. We’re able to switch between these various viewpoints and beliefs, sometimes very rapidly.

Charles C. Mann, in his excellent book The Wizard and The Prophet, writes that he tends to oscillate between seeing things from two contradictory perspectives. One he calls the wizard perspective, based on the belief that the way forward is in growth and technological fixes. The other is the prophet perspective, grounded in the conviction that we need to reduce our consumption and our population growth. One day, his views are those of the wizard, another day he feels more like a prophet, and some days he simply doesn’t know. This is probably true for many of us.

The importance of stories

There are of course many more and more nuanced views on sustainability than just the extremes of wizards and prophets, or of ecomodernist, neo-romantic or ecopessimist. I use these as examples to illustrate a point: stories are important. They are lenses through which we see the world, and they also determine how we act in it. All stories, however, simplify things, and this can end up blinding us to certain aspects of the world.

In practice, there exists a diversity of viewpoints and explanatory stories, within a society and even in our heads. This diversity is beneficial in many ways, but it can also confuse us, and it can sabotage or slow down effective action. It can even interfere with the identification of what the important problems are that need solving.

When talking about stories, we usually think of fiction, but this is not what I mean here. Stories, in a broader sense, are models of the world that are based on language (including visual and other non-linguistic languages). What we call fiction is just one example of storytelling. Fictional stories are important, they are about aspects of the world that interest or entertain us. A nonfiction story is an attempt to describe a part of the world. The attempt doesn’t necessarily yield an accurate description, though. While we see through the lenses of stories, we rarely examine the lenses themselves, to question their assumptions and their limitations.

Stories can be seen as models of the world, but they are not merely descriptive. Most stories, whether fiction or nonfiction, are also normative. They don’t just portray the world as it is, they also show how we think it should be. Our stories are intimately tied up with our values, the things that we find important. They are also tied up with our goals, the things that we strive for. Stories help determine how we look at the world and how we talk about it. Furthermore they help to determine how we act in it and how we think others should act.

Story clashes

Stories can describe different aspects of the world at different levels. For instance, some stories are mostly functional, while other ones are more emotional. Some try to explain the world as it is, while others are more about articulating or reinforcing values, or about finding meaning. These different stories can coexist in our heads and are not always consistent with each other. In fact they rarely are. And while all stories simplify, often they simplify too much.

For almost as long as I remember, I’ve been fascinated by what we now call sustainability. As a young boy in the 1980s I worried over the uncertain future facing panda bears, rhinos and elephants. I saw how organisations such as Greenpeace directed our attention to industrial pollution. I witnessed in wonder how some governments thought it a good idea to dump nuclear waste into the ocean. I was a teenager during the optimistic 1990s, when the Cold War had ended, Western economies were doing well and some people predicted “the end of history”. All humanity’s problems were to be speedily resolved by the free market. As I studied Environmental Science, “the environment” was rapidly going out of fashion. It seemed, indeed, that most environmental problems had been reduced to technical issues, to be solved by better technology and better management. At the opening of the new millennium, I became fascinated by the upcoming science of complex systems. People around me started paying more attention to climate change, with many arguing that there was, in fact, no such thing. While I was working on my Master’s degree in Theoretical Biology, worries about the future resurfaced. Increasingly people were talking about sustainability and climate. And as I write this, climate change is rapidly becoming a reality for many. Sustainability has grown from a fringe interest of activists and academics to one of the major issues discussed in politics and society at large.

Still, most books, articles and talks on sustainability talk about “the environment” as something out there. Something that needs to be fixed, protected or saved in one way or the other. Discussions about sustainability often seem either technical or superficial, or both. For example, we talk about decoupling carbon emissions from economic growth. We pretend that the “planet will be saved” by reducing plastic packaging or electricity use. We talk about sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Oddly, we often fail to define what exactly the most relevant needs of the present are, or the needs of future generations, or the needs of other, non-human life forms.

There are certainly technical aspects to sustainability but it isn’t primarily a technical problem. It’s an issue of values that touches at the core of what it is to be human. We humans are probably the only species on this planet that is able to make rational plans quite far into the future. What do we want, as individuals, as families, as communities, as societies, as a species, in the short term and in the long term? Do we wish to spend our short lives accumulating as much as possible at the expense of others? Most of us would probably answer this with no. Do we want our species, our societies to grow exponentially until resources run out and then crash, only to start growing again in some kind of “boom and bust” pattern? Probably not. If we do not want this future, why do many of our stories and our ideals not reflect our wishes? One of our most common ideals is still to get rich, so we can stop working and live comfortably. And our most common collective goal is still to sustain economic growth.

The interesting thing about sustainability issues is that they will always disappear, eventually. Unsustainable behaviour, by definition, cannot last forever. We either fix it voluntarily, or it is forced to stop at some point. The difficult question is: what will the collapse of unsustainable behaviour take with it? How much damage are we willing to incur? How do we recognise truly unsustainable behaviour before serious damage is done? And are we willing and able to reduce the perceived “needs” of the present, in order to allow for the needs of future generations, or those of non-human species?

What is sustainability anyway?

As we can see, it is not so straightforward to say what “sustainability” should be about. It is perhaps easier to state what sustainability isn’t. The point of sustainability isn’t to continue what we are doing at the moment. It simply isn’t realistically possible to keep our current resource-intensive societies running indefinitely, not even if we’d manage to drastically reduce our use of resources and our emission of waste products. And even if it were possible to continue current practices, the question is whether we should want to. The current global economic system isn’t very good at providing everyone with their necessities to lead a happy, healthy and stress-free life.

Sustainability also isn’t about preventing human extinction. Even if our most dire predictions will come true, we’d most likely still survive as a species. While it is certainly possible that some calamity will drastically reduce the human population, humans have so far proven to be quite a resilient bunch. Moreover, “not going extinct” is setting the bar a little low, in my opinion. One would hope that we can do better than that.

Maintaining and improving wellbeing

So if our long-term goal isn’t the continuation of current economies and the preservation of our species, what could we be aiming for instead? My proposal is to aim for continuing and improving the wellbeing of both humans and other life-forms. Wellbeing may seem like a vague concept, not much better than “needs”. But as I will try to show in this article series, the concept of wellbeing is a lot more concrete than “needs” or even “happiness”. Wellbeing is connected to physical and mental health. It is, to some extent, the absence of prolonged physical and mental stress. In a highly social species such as humans, it is also connected to a healthy social environment, as well as to our possibilities for self-realisation. Unfortunately we tend to confuse wellbeing with things like comfort, freedom of choice and “welfare” or individual wealth.

We should probably also aim to stabilise our societies. We might not need to “save” the planet, but for our own sake we should stop destroying or degrading our own life-support systems and the things in the world that give us pleasure (which includes much of nature). Probably few people would disagree with this goal. However, social dynamics are rarely guided by rational thinking or common sense. Large and complex societies have their own peculiar dynamics, which are difficult to steer and may not always favour long-term stability. Still, there is much room for improvement. And as we shall see, telling better stories can play a role in this.

Stories as simplifying models

As noted before, stories shape the way we see and understand the world. They are about cause and effect and about what is important. Essentially, stories are simple toy-models of the world, or rather of parts of the world. We build these models in our heads, and we can share them with others, which is a kind of human superpower. Stories help us to simplify the world, which is useful because our brains can only handle so much complexity. Stories give us a sense of identity and purpose and they can help us set priorities.

We tend to prefer simple stories over complicated stories, because simple stories make our lives easier. They can specify which categories of things are “good” or “bad”. This then helps us seek or avoid such good and bad things. Examples of “good vs. bad” stories are not hard to find. They clearly stand out in wartime propaganda, and in most organised religions. But they are also common in other areas of daily life, for instance in political views (e.g. “wokes” vs. moral conservatives), dietary trends (ketogenic diets, veganism, paleo diets) or economics (free markets vs. strong governments). Also the ways in which we think about sustainability are full of “the bad” (flying, eating meat) and “the good” (solar energy, buying local, organic produce, travelling by train). Thinking in terms of good and bad is attractive, it provides a shorthand for moral assessments. Good vs. bad stories also provide a strong sense of shared values that link us to our social groups.

Simple stories provide a feeling of certainty, and we much prefer certainty over uncertainty and doubt. In fact, simplifying stories are so important to us that we will defend them when they are challenged. When we are confronted with evidence that contradicts our main explanatory stories, we often choose to ignore it. Rather than question our internal story, we actively go in search of evidence that will support it, and we try to convince others that our stories are somehow more “true” than theirs.

Stories can be big or small, they can construct utopian ideals for a whole society or describe individuals recycling some of their waste. Still, many stories share similarities in structure. One well-known story arc is the Hero’s Journey. One or more heroes must face and overcome difficulties in order to help their people or loved ones. The majority of Hollywood movies follow this story arc. All of us also construct these types of stories in our heads, all the time. Most of us want our lives to matter. We generally strive to be the hero of our own life stories, working toward some future goal. We want to be remembered when we are gone. If our internal story lines and goals become so separated from reality that we can no longer ignore the growing gap, we can become depressed, until we manage to define new goals or develop a new story line to give our lives renewed direction and meaning.

Shared stories

As a group we construct collective stories to give direction to our societies. One extreme example is the utopian story of Communism, which promised to end inequality by getting rid of private property altogether. A somewhat less extreme example can be found in the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals. These broadly aim to increase well-being for all humans and protect the lives of non-human species. In fact, the concept of “development” or “progress” is in itself a shared story, and a fairly useful one, although it is not without problems. We will examine these problems later, in a separate article.

As I said before, all stories are simplifications. This in itself isn’t a problem. It can become a problem, however, when we forget or ignore the fact that our stories are simplifications. The story of Communism was a simplification. Communist utopia never became a reality and would probably never come. In fact, many communist leaders were perfectly aware of this. Yet they stuck to the story, because it was useful. It provided a common goal, at least in theory. It also provided a shared identity which, for a while at least, kept communist and socialist societies together. The story of Capitalism is a similar kind of simplification. In his well-known book Sapiens, the author and historian Yuval Noah Harari calls such stories “shared fictions”. In his view, ideologies such as Communism and Capitalism are shared fictions, as are all religions, and even things such as “money”, “the government”, “the law” or “the economy”. Shared fictions are concepts and stories that we collectively believe in and that therefore, through our collective actions, have real power in the world. Shared fictions can also lose their power if we stop believing in them, as when currencies collapse again and again throughout history. However, as long as they persist, shared fictions are very powerful tools to coordinate collective action within human societies. Humans are storytelling animals, it is our superpower. It is also the cause of much suffering and many problems.

Shared stories are very hard to change, because they are distributed over a great many minds. Moreover, our shared stories are tied up with our shared identities. This is important for binding people together within a society. But it can also cause us to drift apart, because we contrast our identities with “others” outside the social groups we identify with. This can result in polarisation between groups in a society, which in the best case can sabotage collective coordinated action required to solve large-scale problems. In the worst case it can lead to extreme violence between “tribes” of people who base their identity on different stories, different ways of viewing the world and their place in it.

Blind spots

Even if our collective stories don’t lead to polarisation or violence, they can be problematic. They help us to understand and navigate the world, but they also blind us to the parts of the world that do not fit the story line. Our stories lead us to collectively focus on certain problems and connected kinds of solutions. Sometimes this is counterproductive, especially if we try to apply simple stories to situations that are complex, and even more so if we do this on a large scale. An example is the relentless focus on “efficiency”, which has come to dominate much of our global thinking, especially in the 20th century. Thinking in terms of efficiency can be useful, and has proven very powerful in shaping the modern world. But making a system more efficient tends to reduce its diversity and its resilience, which almost always causes problems in the long run. An obvious case in point is the production of food through large-scale monocultures. This is very efficient, at least in terms of product yield per hectare or acre. But obtaining such high yields generally requires large-scale application of fuel, fertiliser, irrigation water and pesticides. Moreover, many of the techniques of modern agriculture have negative effects on the quality of agricultural soils. Consequently, yields have become increasingly sensitive to shortages of water and fertiliser, and to high fuel prices, bad weather and the appearance of new pests. Continuing this trend is unlikely to achieve long-term sustainability. Yet there is a tendency in “ecomodernist” stories to emphasise the need for further increase in agricultural efficiency in order to “feed the world” without expanding agricultural land. At first glance this seems like a sensible idea, but like all stories it’s a simplification that ignores some important complexities of the real world. While it can help solve some problems, it can make other problems worse.

Better stories

The question is, is this really the best we can do? Do we really have to choose between technological optimism or environmental pessimism? I think that we can do better, and I’m not the only one. However, when thinking and talking about sustainability, we do need better stories. If we are to truly address the difficult problems of long-term well-being, wishful thinking will be insufficient. We cannot simply believe that technology or more education or “going back to nature” will fix everything. Equally it won’t help us to believe that our problems are too big to be solved, or that the best solution is the extinction of all humans.

It’s important to realise that our stories aren’t just explanations and problem solving-tools, they are also meaning-making tools and self protection devices, used by people to feel good about themselves. They help determine what we want, how we want it and what we’re willing to give up. Most people want sustainability, but they also want growth (as a perceived part of “progress”), so we prefer “magic bullet” solutions to ones that actually require effort or sacrifice. These magic bullet solutions have shifted through time: from machines to “science” to rational planning to computers to “the market” to cryptocurrencies and the blockchain to artificial intelligence. Besides this, many people want to feel that they’re the hero that is “saving the world” in some way. This in itself is not bad, but unfortunately most of the real problems we face do not require an individual to “save the world”. Instead they require hard work done collectively by many, many groups of people, who need to coordinate locally, regionally and globally to analyse and solve many small problems, preferably without causing a lot of new problems in the process. Much of this work is already being done by people somewhere and we can learn from their experiences and scale up our collective effort on solutions that really work.

In this series of articles I will look for better stories. Over the years, many people have come up with different and occasionally non-conventional ways of looking at and talking about sustainability, about the nature of our main problems and the direction of possible solutions. I believe that some of these ideas are useful, and may inform more constructive ways of thinking and talking. They may help us build better stories. They may help bridge the gaps between ecomodernist, neo-romantic and ecopessimist ways of seeing the world.

Science as starting point

Science of course is one tool that may help us. The neat thing about science is that it provides a toolbox for testing if our explanatory stories are useful, based on observations and experiments. The stories of science are often the best explanations we have for how the world works. Still, these stories of science are necessarily simplifications, that may be inaccurate and may miss important aspects of the world. And scientific stories describing complex realities rarely offer single or simple explanations. Rather they offer sets of likely alternatives. As with all stories, when offered a choice between alternatives, we tend to pick the explanations that suit us best. Still, at least the explanatory stories of science constantly evolve as new observations are made and some explanations are shown to be incomplete or incorrect. Therefore, it is to science that we shall turn first. Specifically in the next articles we will look at the fairly young science of complex systems. We will also examine some reasons why biological life is so robust that it has managed not just to survive but to flourish, despite several truly cataclysmic events that occurred over the long history of our planet.

Do you want to be notified when future articles in this series are published? Subscribe to my Substack, or follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky or Twitter/X. You can also subscribe to our Atom-feed.

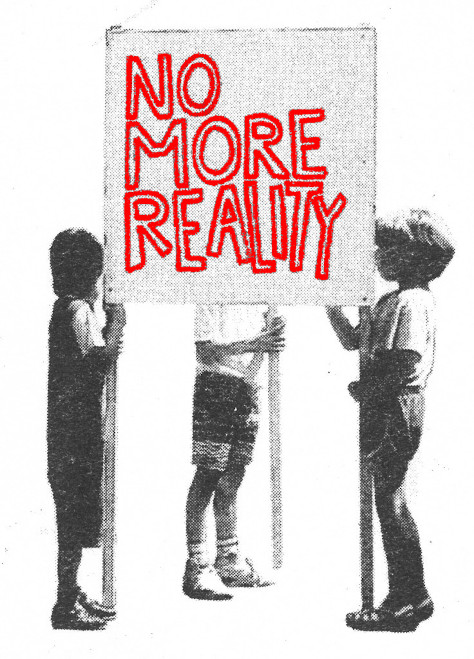

Image credit: Bigoudis

Further reading

Storr, Will. The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better. Abrams, 2020.

https://www.thescienceofstorytelling.com/

Gottschall, Jonathan. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

https://www.jonathangottschall.com/storytelling-animal

Mann, Charles C. The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World. Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.

Kallis, Giorgos. Limits: Why Malthus Was Wrong and Why Environmentalists Should Care. Stanford University Press, 2019.

https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=29999

Economist Giorgos Kallis makes the important point that self-imposed limits should probably be

set voluntarily by societies, based on values. If we wait for limits to be imposed externally by our environment, we greatly reduce our options for acting in ways that align with what is important to us.

Damasio, Antonio. Feeling and Knowing: Making Minds Conscious. Hachette UK, 2021.

In this short book, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio argues that feelings

and consciousness arose in humans and other animals to help us determine

how well our life process is going, and to act on that information. We

all seek wellbeing, because a feeling of wellbeing signals that all is

well, while feelings of stress or pain signal that there may be a

problem.

Mitchell, Kevin J. Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will. Princeton University Press, 2023.

https://www.kjmitchell.com/books

Much of this book is about whether free will exists. But neurobiologist and genetics researcher Kevin J. Mitchell also gives a clear and very readable description of how all organisms, ranging from microbes to roundworms to humans, build internal models of the world. These models are embodied in neural networks and other physiological structures and allow living beings to do things, to act as agents that can cause things to happen, driven by internal goals.

Blackburn, Simon. Ethics: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2021.

https://academic.oup.com/book/31834

This short introduction to ethics nicely illustrates how we construct stories about which things are good and which things are bad. Simon Blackburn points out that such stories are important in guiding our sense of morality, but that we need to be aware of their limitations and assumptions as well.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Random House, 2014.

https://www.ynharari.com/book/sapiens-2/

In his bestseller about the history of humankind, Harari introduces the useful concept of “shared fictions”, which can act as a tool for coordinating the values, goals and activities of large groups of people.

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300246759/seeing-like-a-state/

The political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott has pointed out that our goals determine how we structure the world, and also what our blind spots are. He shows how “scientific” foresters of the 19th century and the modernist states of the 20th century simplified the social and natural systems they worked with, in the name of efficiency, rationality and the pursuit of a utopian future. In doing so, they destroyed much of the ecological and social fabric required for systems to function well. They failed to appreciate that the “messiness” of real ecological and social systems actually contributes to their long-term resilience.

Vandermeer, John. The Ecology of Agroecosystems. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011.

Biologist John Vandermeer argues that agricultural production systems are ecosystems that are to a large extent structured by humans. Agriculture is fundamentally different from an industrial production system, because agriculture is an open system in which biological, physical and chemical processes still play an important role. We cannot fully control these processes, and in fact, our attempts to do so often end up making problems worse, because they degrade natural controls and cycles. Instead of trying to maximise control, we should use ecological knowledge and try to work with natural structures and mechanisms to stabilise agricultural productivity, reduce pests and prevent the degradation of agricultural soils.

Solnit, Rebecca. ‘If You Win the Popular Imagination, You Change the Game’: Why We Need New Stories on Climate. The Guardian, January 12, 2023, sec. News.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/jan/12/rebecca-solnit-climate-crisis-popular-imagination-why-we-need-new-stories

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

https://www.dukeupress.edu/staying-with-the-trouble

The work of interdisciplinary ecofeminist scholar Donna Haraway isn’t very accessible to the general public, indeed one commenter called it a “postmodern word salad”. This is unfortunate, because readers who manage to struggle through the somewhat abstruse but also highly original and sometimes quite poetic language of Haraway can find much of interest in her writing and talks. Among many other things, she argues that we suffer from a lack of imagination in the ways we currently think and talk about sustainability. Many of our current discussions rest on either wishful thinking or on fatalism, both of which are unhelpful. She criticises the false certainties and human exceptionalism that characterise many of our narratives. Instead, we should think outside of the box and we should connect with and listen to others (including other species). According to Haraway we should also pay more attention to context, and to small personal-level stories that refuse to yield to big utopian, technocratic or apocalyptic narratives.